Understanding Trauma-Induced Memory Loss

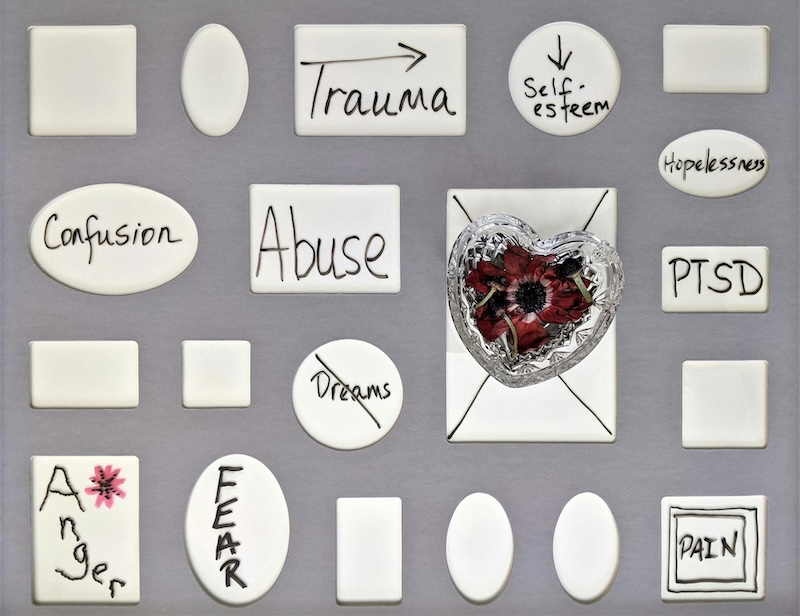

Trauma-induced memory loss is multi-layered and complex. It is often described as a dissociation or vertical split in consciousness, separating behavior, affect, sensation, and knowledge (BASK). Dissociative defenses—primarily developed to keep a person safe—break the traumatic experience into fragments that are more manageable, but are reinforced by amnesiac barriers.

For example, a child or adolescent might act out specific behaviors that seem maladaptive or out of context. However, if these behaviors were connected with the appropriate emotions, sensations, and knowledge, they would make sense. Due to the complexity and ineffability of trauma, these pieces often appear isolated. A child may destructively act out without linking it to abuse, or scream without being conscious of the underlying feelings or sensations.

The goal in therapy is to restore all aspects of the BASK model back to pre-traumatic functioning, where behavior, affect, sensation, and knowledge are seamlessly connected.

The Role of Dissociation in Foster Children

Children and adolescents who experience multiple foster placements often learn to dissociate as a survival mechanism. Repeated ruptures in primary attachment bonds, combined with recurring abuse in various forms, fracture their stable sense of self into independently functioning parts. These fragmented aspects vary in their ability to function autonomously.

In a stable and secure environment, a child can channel psychic energy toward growth and healing. In contrast, disjointed external environments often mirror themselves in the child’s inner structure, leading to further splits in identity and memory.

The Importance of Stability and Safety

Foster care environments vary greatly in their ability to provide consistent, loving, and reliable care. There is no prescriptive formula for success. However, when a child is placed in a foster family that prioritizes safety and compassionate attunement, the results can be deeply reparative.

In such an environment, the child’s innate biological systems—wired for survival at the unconscious level—can recalibrate. Homeostasis is achieved, and the child begins to trust, bond, and emotionally regulate within a secure attachment. This stability allows continuity of memory to be restored as fragmented, post-traumatic aspects of the self integrate, supporting healthier development and growth.